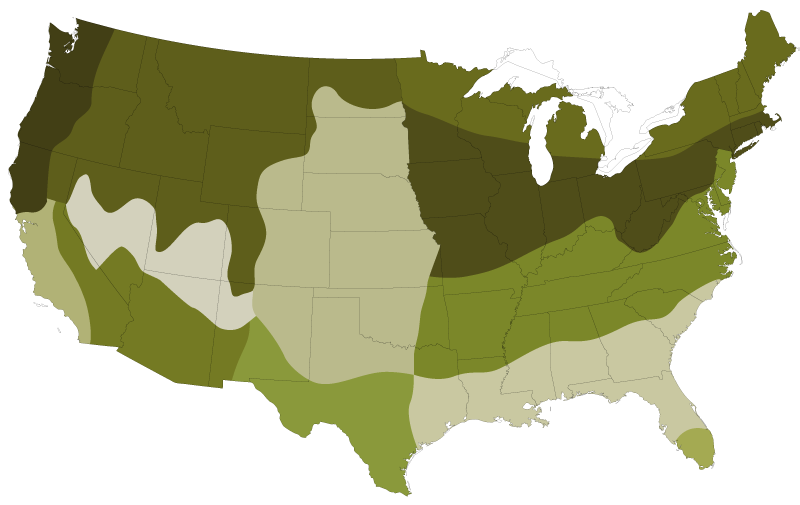

Our team of experts have specially designed blends for each region of the United States. The following considerations were made during the design process for each regional mix:

- Environmental elements such as soil conditions. sun/shade tolerances and heat tolerances.

- Genetic attributes such as color. sod density and disease resistance.

- Water requirements.

What Nature's Seed Customers Say

“This past early spring we planted our backyard with your Triple-Play Tall Fescue Grass Seed Mix. Due to early cool weather it took some time to take off. Now it’s fall and our backyard is lush and green. Very few weeds. Midsummer and fall fertilizer and weed treatment. Beautiful! Highly recommend!”

Scott Cole

“I live in the Pacific Northwest and bought the bee pasture blend…I love it, the bees love it, and my chickens love it. Coming back for more and some other blends. I would highly recommend these products. Thank you!”

Brian Huggins

“It was a real pleasure to order from you! The seeds are sprouting, and the delivery was as promised! Thank you!”

Enid Laursen

Learn From Our Experts

How to Overseed Pasture Seed for a Healthier, More Productive Field

06/19/2025

When your pasture begins to show signs of wear, it may be time to consider overseeding. Patchy growth, excess weeds,

Soil Preparation for Pasture Seeding: Set the Stage for Healthy Growth

06/19/2025

The importance of soil preparation for pasture seeding success cannot be understated. With proper soil preparation methods, your pasture will

Pasture Maintenance Tips: How to Keep Your Forage Healthy Year-Round

06/19/2025

Taking care of pastureland requires more than just overseeding and grazing. Proper pasture maintenance is key to long-term productivity, and

Need More Resources?

From choosing the right grass seed to fertilizing

new lawns, we’ve got you covered.